By Isabell Köster

“Medusa symbolizes something powerful: the horror, the rage, the refusal to conform to beauty or softness. She’s about embracing that darkness rather than hiding it. That’s how I feel on stage too—I’m not trying to look beautiful. I want to be imposing, intimidating even. There’s strength in that. That’s why she resonates with me so strongly.” – Agnes Alder

Photo Credit: Adam Moffat

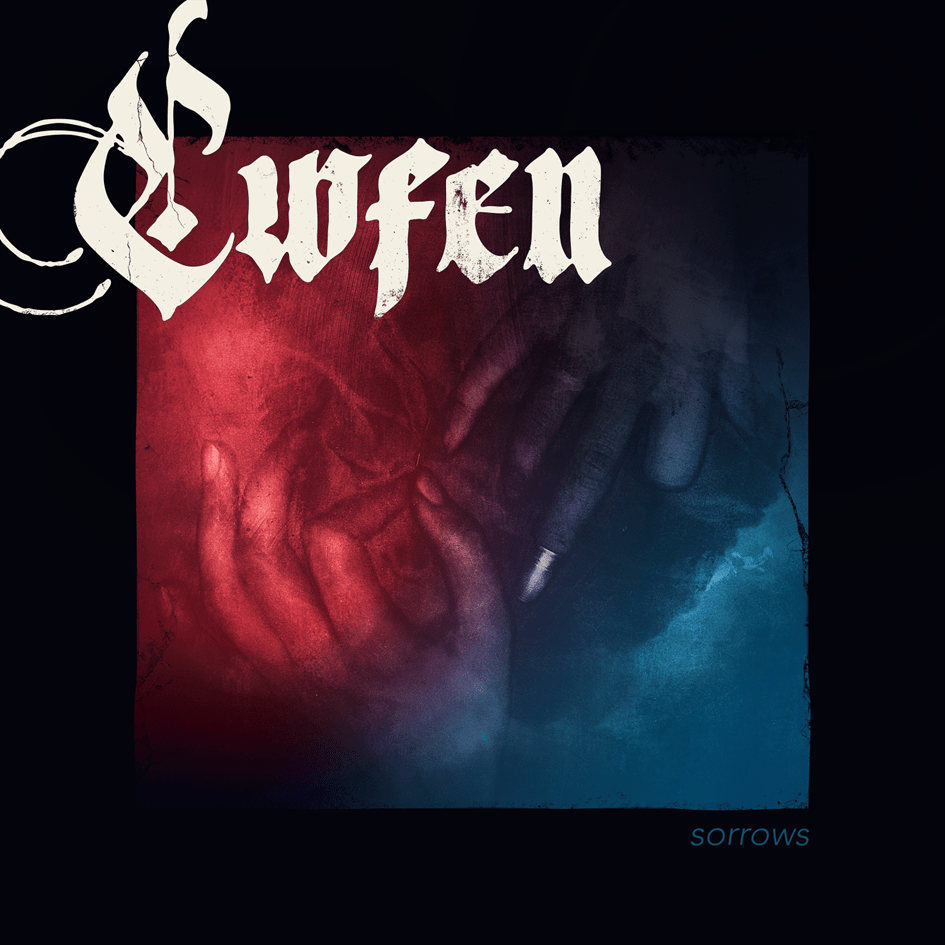

Since emerging from the Glasgow underground just 18 months ago, CWFEN (pronounced: Coven) have been growing not only their reputation but also their fanbase, selling out shows and attracting a growing audience to their doomy fever dream. Their debut single “Reliks”, released in October 2024, was a hit with fans and critics alike and their debut album “Sorrows”, released on May 30, 2025 via New Heavy Sounds, received several glowing reviews – and rightly so!

The Scottish quartet is vocalist and rhythm guitarist Agnes Alder, guitarist Guy deNuit, bassist Mary Thomas Baker and drummer Rös Ranquinn. We recently sat down for a chat with frontwoman Agnes Alder and talked about the roots of CWFEN, her musical influences and her favourite female mythological figure.

Heavy Hags: What motivated you to found CWFEN?

Agnes Alder: I’ve played music for most of my life. I joined my first band when I was about twelve and spent years writing and performing in various forms. But there was a period where I stopped—life just got in the way. When the Covid pandemic hit, it prompted a bit of soul-searching, as it did for a lot of people. It made me reflect on what really matters and what I truly wanted to be doing once things returned to normal. For the first time in a long while, I felt a real urge to write again—and what came out was much heavier than anything I’d written before. At first, it was just a solo project—me, my guitar, my bass, and some drum tracks. Then I wrote a couple of songs and shared them with Guy. He said, “This is really good—you should do something with it.” So, from there, we just kind of beckoned our friends into the band. It was never meant to become what it has—it all happened quite naturally because we loved playing together and realised, we were making something different from anything we’d done before. We thought we’d maybe play one or two shows. But people really connected with it, and we just kept going. And now, here we are.

HH: The first song that I listened to was “Wolfsbane” and I was instantly captivated by the music and lyrics. I read online that it’s about female anger, which I think is necessary nowadays, in the face of rising extremism and conservatism everywhere. Tell me a bit more about the song, please.

AA: “Wolfsbane” — I’m so pleased that song is resonating with people. I wasn’t in an angry place when I wrote it — it was something beyond anger. I’ve been a feminist for a long time, and I guess I’m old enough now that I’ve seen progress… and then, for the first time, I saw things moving backwards. I felt this deep, bodily anger — watching what was happening to the LGBTQ+ community and just seeing all of it unfold. For me, writing is about getting the feelings out of my body — that’s where most of the songs come from. And part of me felt like: we’ve been polite about this for a long time. We’ve asked nicely. We’ve written things. We’ve used all the ‘acceptable’ channels to try and get people to listen. And it’s not working. It’s not cutting through anymore.

Art — whether it’s music or any other creative expression — has always been, for me, a way not just to channel emotion, but to respond to the world around us. When I was writing “Wolfsbane”, I was writing it for myself, for my daughter, for my friends — imagining something provocative. Like: what if we just poisoned all the men? Obviously not literally, but it was about speculating — saying the thing you wouldn’t be allowed to say in polite company, in writing, or out loud. What if a song could hold that rage, that frustration — and make people think differently about whether politeness is still appropriate in the face of everything that’s happening? It’s a song I really enjoy performing — especially live, because you can see how the women in the crowd respond. There’s something cathartic about screaming in men’s faces.

HH: Where did you film the video for “Wolfsbane”?

AA: There’s a ruined castle near a residential area in Glasgow. Scotland has many random castles, which is very cool. We take it for granted living here. For the video, we needed a spooky, gloomy place with few visitors. Our friend Richie, who did the filming, suggested it. We said, “It looks good; we’ll come and see.” He was right. It was a large vault space, and you could climb up to some of the castle’s ruined floors. Since the flooring was missing, you could look down. I’m afraid of heights, so I didn’t go up but did everything on the ground floor. The background was simple, moody, with light and shadow, not fully natural light.

HH: You live in Glasgow. Would you say that the city has in any way influenced your music?

AA: Yes, I think it has influenced us in several ways, probably without us even realizing it. The music scene in Glasgow is unique. I’ve lived in other cities, but I’ve never experienced anything quite like this—especially in the heavy music scene. People don’t stick to their genres. Death metal fans will come to your shows. Goths, old-school hard rock fans with battle jackets—they all show up. People genuinely support each other. There’s a lot of exciting stuff happening in Glasgow right now. You’ve got bands like Mrs Frighthouse, Coffin Mulch, and others doing something very different from the rest of the UK. We all go to each other’s gigs. We’re friends now, and seeing what others are doing pushes us to raise our game. There’s a great sense of creative cross-pollination.

Glasgow is also a working-class city with politics at the forefront. It’s very left-leaning, pro-immigrant, pro-social justice, and queer-friendly. That mindset is part of the city’s DNA. If we were making this music elsewhere, it might not be received the same way. But here, it resonates because the environment fosters that kind of expression. This is a city that actively participates—whether it’s protesting against anti-abortion campaigners who try to intimidate people at clinics, supporting Palestine, or advocating for LGBTQ+ rights. When you’re surrounded by that passion and activism, it naturally influences the art you create. There may not be a single “Glasgow sound,” but there’s a powerful mix of a vibrant music scene, social consciousness, and working-class roots that shape what comes out of it.

HH: “Sorrows” has just been released. When and why did you choose this title?

AA: The title came together quickly after the album was finished and we’d spent some time listening to it. I didn’t want to rush into choosing a name—I wanted to sit with it for a while. It felt like an album of lament. In Scottish culture, laments have a deep history—sad songs used for grieving, mourning, or storytelling. That resonated with me, especially in terms of the narrative aspect of the music. Still, the word “lament” didn’t quite feel right. Then, in a moment of unexpected inspiration—when I wasn’t actively thinking about it—the word “Sorrows” came to me. I saw it clearly, as if the album had named itself. I went back to the band, much like I did with our band name, and said, “This is the album title.” Whether it was my conviction or that it simply felt right, they immediately agreed. The emotional impact of the album stayed with me. Although it’s only just been released, I’ve been listening to it for about a year through the mixing process. The songs felt like a mirror, teaching me about the emotions I was experiencing. When I listened back, I realized there was real weight to the music—not because all the songs are sad, but because they hold a time capsule of intense feelings. “Sorrows” just felt like the right word to capture that.

HH: Is there an underlying concept that connects the songs?

AA: I always write from the point of view of a feeling. Whether I start with a riff, a melody, or a lyric, it usually stems from an emotion triggered by something else. I read a lot, so it’s often books, art, news, or history that sparks that urge to write. The songs aren’t linked by a central concept—it’s not a concept album—but they’re unified by expressions of sorrow in different forms. Some reflect personal experiences, like the loss of belief and the vulnerability that follows. Others respond to events in the world. “Wolfsbane” and “Rite” fall into that category.

“Embers” is the one that makes me cry every time I sing it—I even cried while recording it. It’s about women falling in love at a time when doing so meant persecution. It still does in many places. That theme feels especially urgent now. There are historical elements, political themes, and personal reflections throughout. But I don’t see the songs as being about me or my life. It feels more like I’m channelling something—just the messenger. That distance helps me sing them more freely, with fewer inhibitions. When I was younger, my songwriting was more introspective. Now, it feels like a response to the world around me. At nearly 38, I’ve lived more, felt more, seen more. I don’t feel the need to be literal. I can just sit with the feeling and let the song emerge from that.

HH: Maybe you can tell me a bit more about what, for example, “Bodies” is about. It’s an interesting track.

AA: “Bodies” came from a slightly different place. The first two songs I wrote for the band were “Wolfsbane” and “Bodies”, written back-to-back over two days in the studio. I think “Bodies” came first, and it was more of a speculative exercise. At the time, I was reading a lot of philosophy and thinking about the idea that women are expected to create—to produce, to have children. I’d been dealing with some personal health issues and reflecting on all of that. The question that emerged was: what if there were a vast, feminine energy that wasn’t small or passive—not something designed just to produce, but something powerful and consuming, almost on a cosmic scale?

That idea led me to the concept of the “monstrous feminine.” The lyrics — “I am the darkness”— were my way of flipping the narrative. What if I could sing from the perspective of everything women are taught not to be? That defiance felt important. I think that shift in perspective is also shaped by where I am in life. I have an adult daughter now, and I see her navigating the same challenges I once faced. I don’t feel the need to be polite anymore — or to care what people expect. So “Bodies” came from a place of imagining the feminine not as a gentle creator, but as a powerful destroyer – an act of resistance in itself.

HH: You also have a Medusa tattoo on your chest. Do you have a favourite female mythological character?

AA: I have a large tattoo of Themis—the Greek goddess of justice—on my thigh as well, but Medusa is the figure who resonates with me the most. It ties back to the idea of the monstrous feminine. There’s a brilliant book by Natalie Haynes called “Stone Blind”, where she retells Medusa’s story with more nuance and empathy.

I’ve been fascinated by Greek mythology since I was a child—ever since watching “Jason and the Argonauts”. In the original myths, Medusa is portrayed as this terrifying figure—so ugly that looking at her turns a man to stone. But there’s something deeply perverse about how that image was used. Roman soldiers wore her likeness on their armour for protection. So, there’s this contradiction: denigrating a woman while using her power for your own safety. To me, Medusa represents a figure whose story has been twisted and maligned. She wasn’t born a monster—she was made into one. She was raped and then punished for it, while the man, the god Poseidon, walked away unscathed. That injustice speaks to me deeply, especially from the feminist perspective I carry at this stage in my life.

Medusa symbolizes something powerful: the horror, the rage, the refusal to conform to beauty or softness. She’s about embracing that darkness rather than hiding it. That’s how I feel on stage too—I’m not trying to look beautiful. I want to be imposing, intimidating even. There’s strength in that. That’s why she resonates with me so strongly.

HH: I think one of the most painful parts of the Medusa story is that she’s punished by a woman. That always struck me as the deepest betrayal—that another woman would do that to her. Medusa is a victim, and yet she’s the one who’s blamed and transformed into a monster. That aspect of the story has always stayed with me.

AA: That’s also why I love the new Medusa statue so much—the one where she’s holding the head of Perseus. I almost got it tattooed at one point but thought that might be pushing it a little. Still, I find it incredibly powerful. What happened to Medusa was cruel on so many levels. And as women, when we really engage with the story beyond the simplified version we’re taught, we start to see ourselves in it. We recognize parts of our own lives and experiences in her. That’s why the story continues to resonate—it speaks to injustice, survival, and reclaiming power.

HH: How would you describe “Sorrows” musically?

AA: It’s difficult to put what we do into a single category. I know people have started using the term “doomgaze,” which is nice—but we’re not actually shoegaze fans. We just love reverb and spaciousness. What people tend to say about our music is that it feels emotionally heavy—not just sonically heavy. There’s light and dark. The album is full of contrasts: tender moments, explosive ones. It’s expansive and, I’d say, quite lively too. Most of it was recorded live, with only a few overdubs. A lot of the takes are first takes. We didn’t isolate instruments—we played together as a band, like we do on stage. We used room mics and production techniques you’re probably “not supposed to” use, but they gave it atmosphere and energy. The sound touches on several genres without fully belonging to any of them. People hear goth, black metal, even dreamier textures. But to me, it’s more about a sonic palette—we work with a specific set of colours, and with those, we paint very different pictures. Some songs are quiet and introspective, others like “Wolfsbane” are more rabble-rousing, and then you have something deeply emotional like “Embers”. Each track sounds like us, but none of them sound the same.

HH: I read that you started doing harsh vocals only like during the pandemic. How did you get into that?

AA: I taught myself how to do that—entirely on my own, in my car and in the shower. So, apologies to my neighbours. It definitely hurt at first.

Why did I do it? Honestly, it was a response to big emotions, to everything happening in the world. I’ve always listened to a lot of heavy music. My taste is broad—I love black metal, Diamanda Galás, anything that feels slightly unhinged. For me, harsh vocals aren’t about sounding aggressive for the sake of it. They’re a way to express intense emotion—something deeper. I’ve sung since I was a child. I was in choirs at school and church, like many kids, and my music teacher taught me to sing properly from the diaphragm. I’ve always had an alto voice, powerful but not suited for soft or “pretty” songs. So singing was always something I did privately, for myself. But then I started seeing other women doing these intense, harsh vocals, and I wondered: could I learn to do that safely? I watched videos, practiced, and surprisingly, it came to me quickly. I think it helped that I was already trained in diaphragmatic breathing and was very conscious about protecting my voice. The first time I did it properly, I shocked myself. I’d never heard a sound like that come out of my body. I remember trying it during practice in front of the band—I just said, “I’m going to try something,” and let out this huge noise. Their reaction said it all. Since then, I’ve kept going. It’s now one of the things I enjoy most, and I’m proud of being able to switch between harsh and clean vocals so fluidly. It feels like I’m using my whole instrument—and it’s been a really fulfilling journey.

HH: You stated that listen to many different styles of music. Which bands or artists are your all-time favourites?

AA: Gosh, this is hard to pick. I love heavy music, but I also grew up in a house with goth, new romantics, punk, and glam rock. If I had to choose my absolute favourites… Nirvana was the first band that made me want to buy an electric guitar. I had an acoustic before, then someone gave me “Nevermind” and it changed everything. So, they’re number one. PJ Harvey is another. Around the same time, I was given “Rid of Me”, and it blew my mind—spiky, weird songs, and seeing a woman with a guitar, which was rare back then. I also love Type O Negative. As problematic as they are in some ways, their music was huge for me as a young goth. And Nick Cave—I absolutely love him. Outside of typical genres, Bohren & der Club of Gore is one of my favourites—doom jazz at its best. I also love Hildegard of Bingen—early spiritual, sacred music. I listen to so much and draw from all over. I’m a musical magpie, really. It changes all the time, but those are the artists who’ve consistently meant the most to me. ■

Leave a comment